The brain holds a ‘map’ of the body that remains unchanged even after a limb has been amputated, contrary to the prevailing view that it rearranges itself to compensate for the loss, according to new research from scientists in the UK and US.

The findings, published today in Nature Neuroscience, have implications for the treatment of ‘phantom limb’ pain, but also suggest that controlling robotic replacement limbs via neural interfaces may be more straightforward than previously thought.

Studies have previously shown that within an area of the brain known as the somatosensory cortex there exists a map of the body, with different regions corresponding to different body parts. These maps are responsible for processing sensory information, such as touch, temperate and pain, as well as body position. For example, if you touch something hot with your hand, this will activate a particular region of the brain; if you stub your toe, a different region activates.

For decades now, the commonly-accepted view among neuroscientists has been that following amputation of a limb, neighbouring regions rearrange and essentially take over the area previously assigned to the now missing limb. This has relied on evidence from studies carried out after amputation, without comparing activity in the brain maps beforehand.

But this has presented a conundrum. Most amputees report phantom sensations, a feeling that the limb is still in place – this can also lead to sensations such as itching or pain in the missing limb. Also, brain imaging studies where amputees have been asked to ‘move’ their missing fingers have shown brain patterns resembling those of able-bodied individuals.

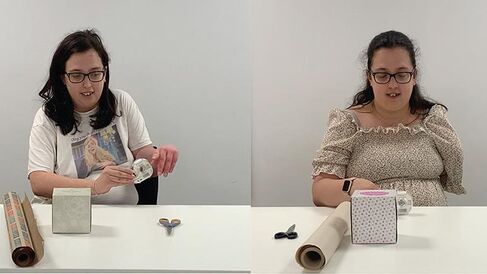

To investigate this contradiction, a team led by Professor Tamar Makin from the University of Cambridge and Dr Hunter Schone from the University of Pittsburgh followed three individuals due to undergo amputation of one of their hands. This is the first time a study has looked at the hand and face maps of individuals both before and after amputation. Most of the work was carried out while Professor Makin and Dr Schone were at UCL.

Read more here