Scientists from the University of Cambridge have developed a platform that uses nanoparticles known as metal-organic frameworks to deliver a promising anti-cancer agent to cells.

We focus on difficult diseases such as hard-to-treat cancers for which there has been no improvement in treatment in the last 20 years

David Fairen-Jimenez

Research led by Dr David Fairen-Jimenez, from the Cambridge Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, indicates metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) could present a viable platform for delivering a potent anti-cancer agent, known as siRNA, to cells.

Small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA), has the potential to inhibit overexpressed cancer-causing genes, and has become an increasing focus for scientists on the hunt for new cancer treatments.

Fairen-Jimenez’s group used computational simulations to find a MOF with the perfect pore size to carry an siRNA molecule, and that would breakdown once inside a cell, releasing the siRNA to its target. Their results were published today in Cell Press journal Chem.

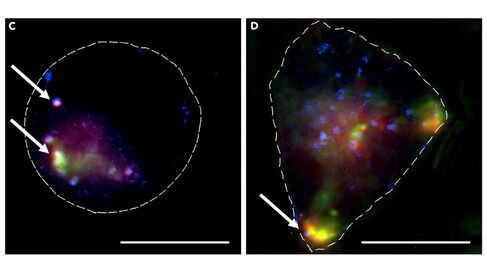

The Cambridge researchers have used a special nanoparticle to protect and deliver siRNA to cells, where they show its ability to inhibit a specific target gene.

Fairen-Jimenez leads research into advanced materials, with a particular focus on MOFs: self-assembling 3D compounds made of metallic and organic building blocks connected together.

There are thousands of different types of MOFs that researchers can make – there are currently more than 84,000 MOF structures in the Cambridge Structural Database with 1000 new structures published each month – and their properties can be tuned for specific purposes. By changing different components of the MOF structure, researchers can create MOFs with different pore sizes, stabilities and toxicities, enabling them to design structures that can carry molecules such as siRNAs into cells without harmful side effects.

“With traditional cancer therapy if you’re designing new drugs to treat the system, these can have different behaviours, geometries, sizes, and so you’d need a MOF that is optimal for each of these individual drugs,” says Fairen-Jimenez. “But for siRNA, once you develop one MOF that is useful, you can in principle use this for a range of different siRNA sequences, treating different diseases.”

A problem with using MOFs or other vehicles to carry small molecules into cells is that they are often stopped by the cells on the way to their target. This process is known as endosomal entrapment and is essentially a defence mechanism against unwanted components entering the cell. Fairen-Jimenez’s team added extra components to their MOF to stop them being trapped on their way into the cell, and with this, could ensure the siRNA reached its target.

“One of the questions we get asked a lot is ‘why do you want to use a metal-organic framework for healthcare?’, because there are metals involved that might sound harmful to the body,” says Fairen-Jimenez. “But we focus on difficult diseases such as hard-to-treat cancers for which there has been no improvement in treatment in the last 20 years. We need to have something that can offer a solution; just extra years of life will be very welcome.”

To read the full article, please visist the University of Cambridge website.